Mediterranean Palaeoceanography and Palaeoclimate

Eelco J. Rohling

Southampton Oceanography Centre,

University of Southampton

United Kingdom

Extended abstract

Being a semi-enclosed marginal basin of relatively small volume (compared with

the open ocean), the Mediterranean shows amplified and very rapid response to

climate change. Consequently, climate signals are well expressed in the Mediterranean,

and in the case of the glacial-interglacial contrast in stable oxygen isotope

records, for example, the Mediterranean shows a signal amplitude that is twice

that observed in the open ocean. The Mediterranean also shows generally elevated

sedimentation rates, and reduced sediment mixing by bioturbation, relative to

the open ocean, especially during the special times in the past when the bottom

waters became anoxic. These attributes make the Mediterranean an excellent basin

for the investigation of changes in past climate and hydrographic response,

at high (decadal- to centennial-scale) temporal resolutions.

There is particular interest in the history of Mediterranean oceanographic

developments because the basin occasionally shows organic-rich sediments (“sapropels”)

that lack any sign of benthic life: these were deposited during periods of several

thousands of years of (almost) completely anoxic bottom-water conditions. This

offers a stark contrast with the modern well-oxygenated bottom-water conditions

throughout the basin. We now know that such conditions recurred at times when

the Northern Hemisphere insolation reached distinct maxima, controlled by periodic

variations in earth’s position and orbital characteristics relative to

the sun. Favourable conditions for sapropel deposition tend to develop roughly

every 21,000 years. The most recent sapropel was deposited between nine and

six thousand years ago. The insolation maxima were especially effective in enhancing

the summer monsoons on the northern hemisphere, and the African monsoon is known

to have been strongly intensified at times of sapropel depositions, discharging

into the eastern Mediterranean via the Nile and likely wadi-type discharge systems

along the wider N African margin. The northern borderlands of the Mediterranean

also experienced much more summer humidity than today. This cannot be address

in terms of the monsoons, and likely reflects precipitation originating from

evaporation over the Mediterranean basin itself. Sapropel formation was most

distinct in the eastern Mediterranean, and the following concentrates on that

region.

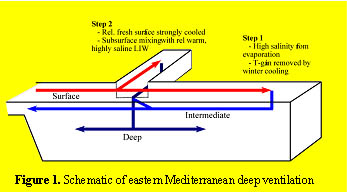

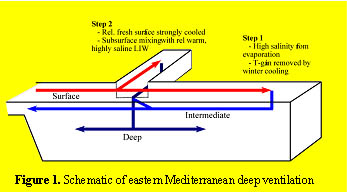

Before evaluating the relationship between enhanced humidity/runoff and a

change in deep-water oxygenation, a schematic view is needed of the modern deep-water

ventilation in the basin (Fig. 1). Inflowing surface water is subject to high

evaporation (and warming) through its pathway. Winter cooling of the high-salinity

surface water in the Rhodes-Cyprus area causes it to sink to form intermediate

water.  The net

forcing behind intermediate water formation, the “first step/stage”

of deep ventilation, is predominantly the salinity gain due to net evaporation.

Intermediate water spreads throughout the basin at ~150/ 200 to 600 m depth,

and in the southern Adriatic Sea this high-salinity but relatively warm water

mass mixes with waters that are of lower salinity, but cooler, and which originate

from strong winter cooling in the N Adriatic. The mixing endproduct is a dense,

relatively high salinity, relatively cool, water mass that spreads below the

intermediate waters to the greatest depths of the eastern Mediterranean. This

“second stage” in the deep ventilation process is predominantly

related to cooling. Without the salt supplied by the intermediate water, the

cooling would not suffice to create sufficiently dense water to ventilate the

basin down to the bottom. Note that this is a very simplified portrayal of the

deep ventilation, which in reality is driven from variety of regions and by

subtle temperature and evaporation shifts, but it offers a useful concept with

which to approach the dramatic changes that occurred in the past.

The net

forcing behind intermediate water formation, the “first step/stage”

of deep ventilation, is predominantly the salinity gain due to net evaporation.

Intermediate water spreads throughout the basin at ~150/ 200 to 600 m depth,

and in the southern Adriatic Sea this high-salinity but relatively warm water

mass mixes with waters that are of lower salinity, but cooler, and which originate

from strong winter cooling in the N Adriatic. The mixing endproduct is a dense,

relatively high salinity, relatively cool, water mass that spreads below the

intermediate waters to the greatest depths of the eastern Mediterranean. This

“second stage” in the deep ventilation process is predominantly

related to cooling. Without the salt supplied by the intermediate water, the

cooling would not suffice to create sufficiently dense water to ventilate the

basin down to the bottom. Note that this is a very simplified portrayal of the

deep ventilation, which in reality is driven from variety of regions and by

subtle temperature and evaporation shifts, but it offers a useful concept with

which to approach the dramatic changes that occurred in the past.

At times of

sapropel formation, the strong humidity/runoff increase affecting the basin

caused a serious reduction in the net evaporation that is so critical in the

first stage of deep ventilation. Conceptual reconstructions, supported by Ocean

General Circulation Models suggest that the salty intermediate water would consequently

have collapsed (Fig. 2). Without its salt-supply, the deep ventilation from

the Adriatic Sea could penetrate only to shallow intermediate depths, reaching

about 400 m. Below that level, there was very limited or no ventilation and

ongoing oxygen consumption rendered the stagnant “old” deep water

virtually anoxic within a matter of centuries. Organic matter that rapidly sank

to the sea floor was no longer subject to oxidation in this old deep water mass,

and it consequently became preserved and buried in the sediments – a sapropel

was being deposited. Here, it needs to be mentioned that productivity during

these events was also enhanced relative to the present, so the organic flux

was increased, which augmented its concentrations in the sediments.

At times of

sapropel formation, the strong humidity/runoff increase affecting the basin

caused a serious reduction in the net evaporation that is so critical in the

first stage of deep ventilation. Conceptual reconstructions, supported by Ocean

General Circulation Models suggest that the salty intermediate water would consequently

have collapsed (Fig. 2). Without its salt-supply, the deep ventilation from

the Adriatic Sea could penetrate only to shallow intermediate depths, reaching

about 400 m. Below that level, there was very limited or no ventilation and

ongoing oxygen consumption rendered the stagnant “old” deep water

virtually anoxic within a matter of centuries. Organic matter that rapidly sank

to the sea floor was no longer subject to oxidation in this old deep water mass,

and it consequently became preserved and buried in the sediments – a sapropel

was being deposited. Here, it needs to be mentioned that productivity during

these events was also enhanced relative to the present, so the organic flux

was increased, which augmented its concentrations in the sediments.

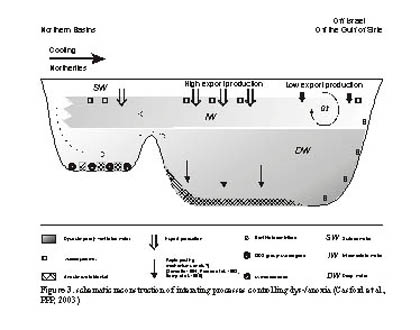

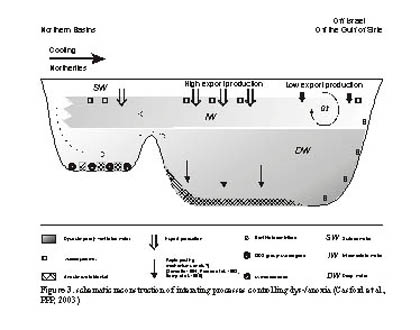

The above reflects the traditional view of the conditions at times of sapropel

deposition, but there have always been nagging doubts about the intensity and

extent of truly anoxic conditions. Having been deposited under (virtually) anoxic

conditions, which precluded benthic life that might otherwise bioturbate the

sediments, many sapropels display the original (seasonal?) sedimentary lamination.

These sediments can therefore be sampled in great detail, to look at variability

on decadal time scales. In a recent study, we have compiled evidence from a

variety of sapropels of different ages, which shows that the anoxic conditions

may have been more intermittent than previously thought, not only in the northern

basins (Aegean and Adriatic), but also in the main body of the eastern Mediterranean.

This would suggest that there were bursts of ventilation to greater depths (as

it seems in some cases even down to 2000 m), which were sufficient to allow

flourishings of benthic organisms that are not low-oxygen adapted. Since a truly

anoxic water column would be full of chemical elements in a reduced state, all

oxygen from brief burst of ventilation into an anoxic water body would be quickly

“titrated” away, chemically. Consequently, there would be no bio-available

oxygen at depth. The implication of this is that the observed benthic faunas

imply that the bulk of the water column (at least down to 2000 m) was never

completely anoxic, but that true anoxia (as reflected in the sediments) was

restricted to a thin layer of water at/above the sediment surface.  Any

burst of ventilation could temporarily reoxygenate that, leaving sufficient

bio-available oxygen to support the observed faunas (Fig. 3).

Any

burst of ventilation could temporarily reoxygenate that, leaving sufficient

bio-available oxygen to support the observed faunas (Fig. 3).

What were the “bursts” of deep ventilation at times of sapropel

deposition related to? Today, much of the cooling that drives deep ventilation

is achieved by intermittent northerly outbursts of cold and dry polar/continental

air masses, which are orographically channelled over the northern sectors of

the eastern Mediterranean. Given the latitudinal position of the Mediterranean

at the boundary of subtropical and temperate westerly influences, and given

that this position has not changed over the time scales considered here, we

expect these types of outbursts also to have occurred at times of sapropel formation.

There may be some evidence that the frequency/ intensity of such events varies

on decadal time scales (NAO?), and we consider that the evidence found in the

sapropels implies that such decadal-scale variability was a feature in the past

as well. Interestingly, many sapropels show a first period of several centuries

to a millennium of very stable/tranquil conditions, followed by (a) period(s)

of several centuries with very frequent reventilations, and a final episode

of several centuries with stable/tranquil conditions. Is there perhaps a longer-term,

centennial- to millennial-scale organisation in the frequency/intensity of the

cold air outbursts (and, therefore, possibly in the NAO?)? This as yet remains

speculative, but ongoing research should bring some useful clarification.

References

Casford, J.S.L., Rohling, E.J., Abu-Zied, R.H.., Jorissen, F.J., Leng, M., and

Thomson, J. A dynamic concept for eastern Mediterranean circulation and oxygenation

during sapropel formation, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,

190, 103-119, 2003.

Rohling, E.J., The dark secret of the Mediterranean - a case history in past

environmental reconstruction, http://www.soes.soton.ac.uk/staff/ejr/DarkMed/dark-title.html

(November 2001).

Rohling, E.J., De Rijk, S., Myers, P.G., and Haines, K., Palaeoceanography

and numerical modelling: The Mediterranean Sea at times of sapropel formation,

Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ., 181, 135-149, 2000.

Rohling, E.J., Cane, T.R., Cooke, S., Sprovieri, M., Bouloubassi, I., Emeis,

K.C., Schiebel, R., Kroon, D., Jorissen, F.J., Lorre, A., and Kemp, A.E.S. African

monsoon variability during the previous interglacial maximum, Earth Planet.

Sci. Lett., 202, 61-75, 2002.

The net

forcing behind intermediate water formation, the “first step/stage”

of deep ventilation, is predominantly the salinity gain due to net evaporation.

Intermediate water spreads throughout the basin at ~150/ 200 to 600 m depth,

and in the southern Adriatic Sea this high-salinity but relatively warm water

mass mixes with waters that are of lower salinity, but cooler, and which originate

from strong winter cooling in the N Adriatic. The mixing endproduct is a dense,

relatively high salinity, relatively cool, water mass that spreads below the

intermediate waters to the greatest depths of the eastern Mediterranean. This

“second stage” in the deep ventilation process is predominantly

related to cooling. Without the salt supplied by the intermediate water, the

cooling would not suffice to create sufficiently dense water to ventilate the

basin down to the bottom. Note that this is a very simplified portrayal of the

deep ventilation, which in reality is driven from variety of regions and by

subtle temperature and evaporation shifts, but it offers a useful concept with

which to approach the dramatic changes that occurred in the past.

The net

forcing behind intermediate water formation, the “first step/stage”

of deep ventilation, is predominantly the salinity gain due to net evaporation.

Intermediate water spreads throughout the basin at ~150/ 200 to 600 m depth,

and in the southern Adriatic Sea this high-salinity but relatively warm water

mass mixes with waters that are of lower salinity, but cooler, and which originate

from strong winter cooling in the N Adriatic. The mixing endproduct is a dense,

relatively high salinity, relatively cool, water mass that spreads below the

intermediate waters to the greatest depths of the eastern Mediterranean. This

“second stage” in the deep ventilation process is predominantly

related to cooling. Without the salt supplied by the intermediate water, the

cooling would not suffice to create sufficiently dense water to ventilate the

basin down to the bottom. Note that this is a very simplified portrayal of the

deep ventilation, which in reality is driven from variety of regions and by

subtle temperature and evaporation shifts, but it offers a useful concept with

which to approach the dramatic changes that occurred in the past. At times of

sapropel formation, the strong humidity/runoff increase affecting the basin

caused a serious reduction in the net evaporation that is so critical in the

first stage of deep ventilation. Conceptual reconstructions, supported by Ocean

General Circulation Models suggest that the salty intermediate water would consequently

have collapsed (Fig. 2). Without its salt-supply, the deep ventilation from

the Adriatic Sea could penetrate only to shallow intermediate depths, reaching

about 400 m. Below that level, there was very limited or no ventilation and

ongoing oxygen consumption rendered the stagnant “old” deep water

virtually anoxic within a matter of centuries. Organic matter that rapidly sank

to the sea floor was no longer subject to oxidation in this old deep water mass,

and it consequently became preserved and buried in the sediments – a sapropel

was being deposited. Here, it needs to be mentioned that productivity during

these events was also enhanced relative to the present, so the organic flux

was increased, which augmented its concentrations in the sediments.

At times of

sapropel formation, the strong humidity/runoff increase affecting the basin

caused a serious reduction in the net evaporation that is so critical in the

first stage of deep ventilation. Conceptual reconstructions, supported by Ocean

General Circulation Models suggest that the salty intermediate water would consequently

have collapsed (Fig. 2). Without its salt-supply, the deep ventilation from

the Adriatic Sea could penetrate only to shallow intermediate depths, reaching

about 400 m. Below that level, there was very limited or no ventilation and

ongoing oxygen consumption rendered the stagnant “old” deep water

virtually anoxic within a matter of centuries. Organic matter that rapidly sank

to the sea floor was no longer subject to oxidation in this old deep water mass,

and it consequently became preserved and buried in the sediments – a sapropel

was being deposited. Here, it needs to be mentioned that productivity during

these events was also enhanced relative to the present, so the organic flux

was increased, which augmented its concentrations in the sediments. Any

burst of ventilation could temporarily reoxygenate that, leaving sufficient

bio-available oxygen to support the observed faunas (Fig. 3).

Any

burst of ventilation could temporarily reoxygenate that, leaving sufficient

bio-available oxygen to support the observed faunas (Fig. 3).